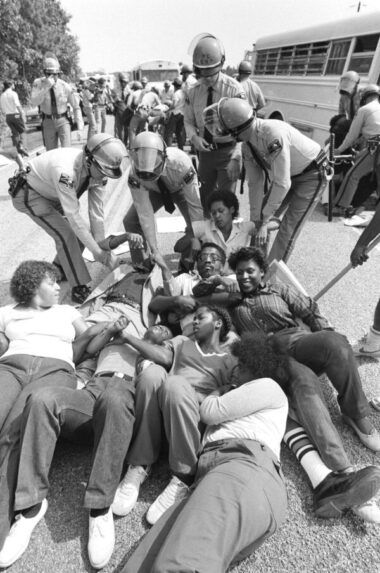

Image caption: 1982, Warren County residents protested a planned toxic landfill in their mostly African American community, considered to be the first “spark” of the national Environmental Justice Movement. (AP Photo/Steve Helber)

Featured article from our latest edition of Clean Currents, Clean Water for NC’s quarterly newsletter providing updates on our program work and ways to get involved with the Environmental Justice movement in North Carolina

Sign up to receive a paper copy of our Newsletter or an e-Newsletter to your inbox!

From the sharp rise in unemployment to the global pandemic impacting us all, tuning into the news this year often feels like opening Pandora’s box. This summer, as NC and other states struggled to flatten the COVID-19 curve, calls for systemic social change gained traction. On Memorial Day, George Floyd, a Black man, died while under the knee of a white Minneapolis police officer. His cries of “I can’t breathe” resonated with millions, catalyzing demonstrations throughout the country and world. Floyd’s death, one among many cases of brutality against Black lives, heightened awareness of the longstanding racial injustices prevalent in the US. Confederate statues have been knocked down and police departments scrutinized for their use of deadly force. Yet, these changes alone are not enough to bring justice. Racism has a pervasive, systemic grip on our society, a fact made obvious not only by unjust killings, but through the ongoing environmental injustices faced by the low-income and minority communities that CWFNC aims to work with to protect their rights.

Spearheaded by people of color in the 1980s, the Environmental Justice (EJ) movement is often regarded as a response to white, mainstream and elite environmentalism. EJ activists continue to bring attention to the unequal

distribution of pollution in the US. A prime example of this discrimination is the recently cancelled Atlantic Coast Pipeline, which was set to cross through many Black, Indigenous, and poor communities in West Virginia, Virginia, and nearly 190 miles of eastern North Carolina.

From the 1982 protests in Warren County, NC (see photo) to block a landfill in one of NC’s poorest counties, with a supermajority of African-American residents, to dump toxic PCB-laced soil that had been removed from roadsides after illegal dumping; to the creation of toxic “sacrifice zones” like the area in western Northampton County where officials seek to attract toxic industries to increase tax revenues at the expense of the health of communities with up to 80% people of color. The EJ movement is more needed than ever. Even last month, our state’s Dept. of Environmental Quality was working to issue a permit for an experimental wood pellet manufacturer—a known source of air pollution—in Duplin County, already heavily impacted by hog operations, nearly 50% African American and LatinX, with the highest rate of Covid-19 infection in the state!

Environmentalists who hold privilege are now shifting to reevaluate their perspectives and empower the voices of those most harmed. “Intersectional environmentalism” vows to promote social justice efforts by supporting activists, communities, and leaders of color. Climate change, a global issue by nature, threatens to increase the disproportionate environmental impacts on vulnerable communities. Groups within the climate justice movement recognize that those facing the brunt of global warming are not its biggest contributors. During this recent uprising against inequality, youth climate initiatives such as the Sunrise Movement and US Youth Climate Strike Coalition stepped forward to support actions for racial equity, too. Meanwhile, organizations that focus on advocacy for people of color— like the NAACP—have been creating programs to fight climate change and environmental injustice for decades.

The acknowledgment that social justice is key to the environmental progress, and vice-versa, leads to breakthrough collaborations. On July 20th, a nationwide “Strike for Black Lives” was the combined effort of social justice, environmental, and labor groups. Although these organizations came to the table with different backgrounds and perspectives, they worked together to acknowledge their differences and organize events across the country. When we support each other, we form an alliance of likeminded folks who recognize and challenge today’s most critical issues. United, these movements have the power to build a healthier, more just planet for us all.