By: Lisa Sorg, NC Policy Watch

April 21, 2021

Environmental advocates want stronger regulation of the potent greenhouse gas, but ag and energy interests are touting biogas

More than 2,200 industrialized hog farms and another 200-plus dairy operations in North Carolina are constantly belching untold amounts of methane, a powerful greenhouse gas and driver of climate change, into the air.

Yet because of the EPA’s inertia and the livestock industry’s significant political power, these farms have eluded any meaningful regulations of their methane emissions and their contribution to the climate crisis.

More than two dozen environmental groups recently petitioned the EPA to regulate industrialized swine and dairy farms as methane emitters under the Clean Air Act. The petitioners, including the North Carolina Environmental Justice Network and the Sierra Club, are asking the agency to classify these operations as “stationary sources” of methane and to be regulated as such.

The success or failure of the EPA petition has significant consequences for North Carolina. The state ranks third in the U.S. in swine production, second in breeding, and second in slaughtering, according to USDA statistics.

Smithfield Foods and Dominion Energy also have deployed a full-court press on lawmakers and state regulators to build expansive new biogas systems, which would be located mostly in communities of color or low-income areas. (Early drafts of the 2021 NC Farm Act had a biogas provision; the bill was pulled from committee earlier this week for further revision.)

And because of its vulnerability to hurricanes, flooding and other extreme weather events, such as heat waves, the state is also on the front lines of the climate crisis.

“… These operations cause and contribute significantly to air and climate pollution that endangers the public health and welfare,” the petition reads. “The EPA has stood idly by for more than 20 years while communities suffer the consequences.”

The petition also targets biogas systems calling them a “false solution,” one that the fossil fuel industry is relying on to “make their … climate impact seem less severe.”

Rachel Gantz, spokeswoman for the National Pork Producers Council, wrote in an email to Policy Watch that, “Unfortunately, the petition recently filed seeking to regulate methane emissions from industrialized swine and dairy operations directly attacks this climate-friendly activity and seeks to halt these innovative practices to capture methane, reversing the years of environmental progress made by U.S. pork producers.”

These biogas systems use anaerobic digesters, in the form of a covered waste lagoon to capture some of the farm’s methane. That gas is then sent through a pipeline system to a conditioning facility, where the biogas is upgraded to natural gas standards, then used by utilities to burn for electricity.

But like natural gas, biogas is not climate friendly. Pipelines leak methane, as do the digesters. However, neither Smithfield nor Dominion has provided data, as requested by state regulators and Policy Watch, showing how much methane the participating farms emit. By having a baseline, it would be possible to more accurately calculate the emissions changes after the digesters are installed.

Gus Simmons, a member of the state’s Energy Policy Council and the engineer behind many of the state’s biogas projects, including Align RNG and Optima KV, did not respond to an email and a voicemail from Policy Watch requesting an interview.

Emissions from big swine and dairy operations remain largely unregulated

Sally Lee is deputy director of rural partnerships of the Government Accountability Project, among the petitioners to the EPA. She described the regulation of methane from industrialized farms as “very urgent and long overdue.”

Many major facilities — such as natural gas compressor stations, landfills, paper mills, furniture factories, and wood pellet plants — are subject to methane regulations as stationary sources, and required to limit their emissions under the Clean Air Act.

Top methane-producing facilities in NC

NC counties with emissions >10 tons in 2018

Source: NC DEQ

Comparatively, big agricultural enterprises have received a regulatory get out of jail card. The nonpartisan Congressional Research Service has reported that, “agricultural operations often have been treated differently from other types of businesses under numerous federal and state laws … some laws are structured in a way that farms escape most if not all of the regulatory impact.”

Pasture-based farms would not be subject to methane regulations. And for industrial dairy and hog operations to be classified as a stationary source, they would have to use a wet manure management system and confine at least 500 cows or 1,000 hogs without access to pasture.

This would affect nearly 90% of the North Carolina’s hog operations and roughly 18% of dairy farms, according to a state livestock permit database.

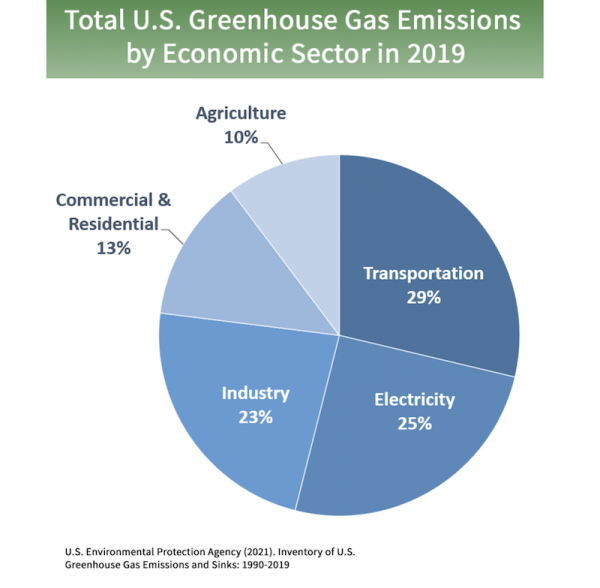

Agriculture accounts for 10% of all greenhouse gas emissions — methane, carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide — in the U.S., according to the EPA.

Since 1990, greenhouse gas emissions from livestock operations have increased by 20.7%, according to the U.S. Greenhouse Gas Inventory, even while overall emissions from all industries has decreased by nearly the same amount.

As for methane specifically, a major source is the waste lagoons, each about the size of a football field, and spray field systems that apply the manure and urine to fields as fertilizer.

Over the same time period, annual methane emissions from these lagoon and spray field systems have increased 49%, according to the EPA, from 15.5 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent (the commonly used unit of measurement) to 23.1 million metric tons. These estimates account for methane reductions from anaerobic digesters.

“Enteric fermentation,” a polite way of describing animal belching and farting, is also a significant methane source. Those emissions increased nationwide by 45%, according to the EPA, from 2 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent to 2.9 million metric tons.

The Clean Air Act requires the EPA to publish and regularly revise a list of categories of stationary sources that, in the administrator’s judgment, “[cause] or contribute significantly to air pollution which may reasonably be anticipated to endanger public health or welfare.”

Methane from industrialized livestock operations, the petitioners argue, does just that because of its role in the climate crisis.

The EPA seems to agree. In 2009, the agency determined that methane, along with five other greenhouse gases, were dangerous pollutants because they cause and contribute to climate change.

When, however, the agency subsequently established standards to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from several industries, big livestock operations were not among them, despite a petition from several public interest groups asking that they be included.

Eight years later in 2017, the EPA declined the groups’ petition, saying it needed more time to gather additional information before determining how to regulate farm emissions. The agency also said it had not yet developed accurate methods to estimate air emissions from the farms, based on data collected during a lengthy, $15 million National Air Emissions Monitoring Study.

Even if they weren’t selected, the 14,000 farms that volunteered to participate in the study — including four swine and one dairy in North Carolina — paid a civil penalty of between $200 to $100,000, based on the size and number of facilities in the operation. They were then temporarily exempt from further federal civil suits. The names of the farms were not disclosed in federal documents.

But the EPA’s explanation for its inaction raises big questions. First, according to several federal reports, including the agency’s Inspector General, the National Air Emissions Study did not include methane. That means the data it collected in the study are irrelevant to whether the agency can move forward on regulating those emissions.

(The study also fell years behind schedule, according to Inspector General and Government Accountability Office reports, and was largely deemed a failure.)

Gantz of the National Pork Producers Council told Policy Watch that further complicating the situation is “that livestock farmers have no way to accurately estimate emissions.”

The council has long advocated for the EPA to complete its review of data from the National Air Emissions Monitoring Study, Gantz wrote, and to complete its development of ways to accurately estimate emissions. “The lack of such methodologies leaves livestock farmers without scientifically valid data to estimate emissions.”

But these methodologies exist, because the EPA already regulates methane on a select number of individual hog farms. The Clean Air Act regulates emissions on those that raise more than 35,000 swine, a fraction of the overall number nationwide.

The EPA already estimates methane from the agricultural sector, based on guidelines by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. However, the EPA doesn’t those apply methods to estimate emissions from individual farms, which can vary based on geography, climate, number of animals and lagoons.

“Systems are out there,” Lee of the Government Accountability Project said. “What we’re saying is, use one of systems.

Biogas: promise v. reality

The 2021 NC Farm Act, sponsored by Sen. Brent Jackson, will contain provisions promoting biogas, according to early drafts now under revision. In addition, the NC Department of Environmental Quality is receiving many applications for biogas upgrading facilities: Align RNG, a Smithfield-Dominion Energy venture would include 19 farms in Sampson and Duplin counties. Those farms would install anaerobic digesters, in effect a covered lagoon, to capture the methane.

That gas would be transported through 30 miles of underground pipeline, which would crisscross many communities of color and low-income areas. The pipeline would connect to an upgrading facility on Highway 24 near Turkey, where it would be conditioned to meet natural gas standards and then injected into a Piedmont pipeline for Duke Energy to use at its energy-generation plants.

But there has been little-to-no transparency about this project. Only four Align RNG farms have been publicly disclosed; Dominion and Smithfield have kept the identities of the rest secret, even from state regulators.

The amount of methane that would be captured is also unclear, as is the leakage that would occur — both directly from the pipeline system and the upgrading facility. Once injected into the Piedmont pipeline, the biogas — and its climate liabilities — will be no different from natural gas. And natural gas pipelines leak, as do compressor stations.

“Methane is such a potent greenhouse gas,” said Joel Porter, policy manager for Clean Air Carolina. “Even losing a little is losing a lot.”

And most of these these farms will still have an open lagoon in addition to a covered one to hold waste. That waste will still be applied via a spray system, emitting methane. Nor do the digesters capture gas emitted by the animals’ intestinal tracts.

“We have an opportunity to do right by these communities, the folks who have been harmed by Big Ag and Big Oil,” Lee said. “We are on the precipice of doing it wrong in North Carolina for biogas.”

The purported economic benefits to the individual farmers has yet to be substantiated. Digesters can cost a minimum of $500,000 and reach into the millions of dollars. To pay for systems, farmers will either have to obtain grants or loans, including those from the USDA, which is taxpayer money. For farmers already in debt, these costs could be too onerous.

The profitability of biogas system also depends on a farmers’ ability to negotiate a contract or power purchase agreement with a utility company, or in the case of Align RNG, Smithfield and Dominion.

Since Duke, and Dominion hold energy monopolies in North Carolina — and Smithfield a near monopoly — the farmers would have precious little bargaining power.

Even if the farmers generate electricity to use strictly on the farm, that process uses internal combustion engines, which themselves emit pollutants like carbon monoxide and sulfur dioxide. A California Air Board Resources study found that 20 biogas systems using internal combustion engines would emit as much nitrogen oxide — smog-forming pollution — as a modern natural gas-fired power plant, but generate only 4% of the electricity.

The EPA has no specific deadline for a response to the petition, only that the agency must do so within “a reasonable amount of time.”

If the EPA grants the petition, it would have to first list industrial dairy and hog operations under the Clean Air Act as stationary sources “that cause or contribute significantly to air pollution that endangers health and welfare.”

Within one year of the listing, EPA must then issue regulations to reduce methane from new and existing operations. The agency would also have to provide guidelines for states to develop standards to reduce methane emissions from existing industrialized farms.

The standards must limit methane emissions using the best available technology, while factoring in the costs.

The petitioners are counting on EPA Administrator Michael Regan, the former DEQ secretary, as well as President Biden to uphold their promise of “following the science” while combating climate change and placing environmental justice at the forefront of their decisions.

“We have a lot of opportunity with the new administration,” Lee said. The inevitability of having to deal with climate change has arrived. There’s a gold rush to cash in on short-term solutions. That’s what we’re seeing with biogas in North Carolina. The industry looks green on the surface but doesn’t require it to clean up its mess.”