Clean Water for North Carolina celebrates the achievements and efforts of communities that continue the fight for justice, equality, and healthy, safe environments to call home. In North Carolina, Black communities have a long history of resilience and activism. The following descriptions, while not comprehensive, offer a brief look into this history and the people, places, and groups that have made a difference.

Princeville, NC was incorporated in 1885 and stands as the oldest town incorporated by Black Americans in the United States, though its place as a community predates that. It was originally known as Freedom Hill and became home to many recently freed Black Americans who struggled in the early stages of segregation and Jim Crow to find a place to live without facing violence in 1865. Sitting on the Tar River south of Tarboro, the land the community had been restricted to was swampy, and residents faced major flooding since its founding. Hurricane Floyd in 1999 and Hurricane Matthew in 2016 hit the community hard, and with the support of many organizations and departments, the Princeville Task Force was created to rebuild the town to be more resistant to flooding while continuing to honor its history.

Source: https://www.wunc.org/post/obstacles-and-support-continue-princeville-rebuilds

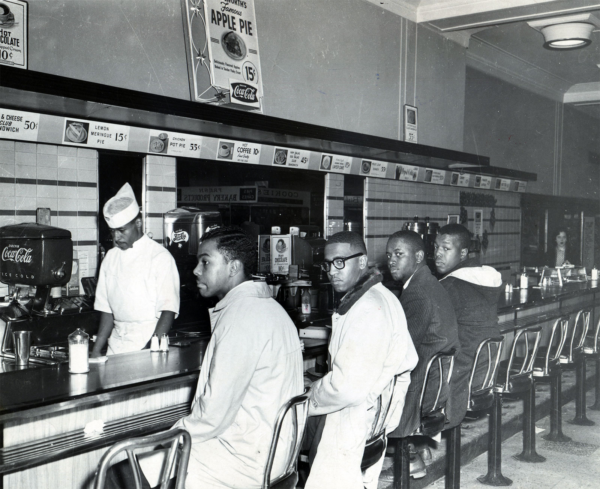

On February 1st, 1960 in Greensboro, NC, a group of young, Black students organized a sit-in at a segregated Woolsworth lunch counter after being refused service. Ezell Blair Jr., David Richmond, Franklin McCain and Joseph McNeil were all students from North Carolina A&T spurred to action by the brutal murder of Emmett Till for supposedly whistling at a white woman. Their sit-in sparked similar nationwide protests, and while many were arrested, the coverage brought increasing attention to the civil rights movement. In response, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee was founded in Raleigh, NC in April 1960, which served as one of the leading forces in the civil rights movement, organizing Freedom Rides, Black voter registration drives and alongside the NAACP pressing for passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Source: https://snccdigital.org/events/sit-ins-greensboro/

In September 1982, Warren County, NC became the stage for protests that would later help define the Environmental Justice movement. The protests were in response to a decision by the state to create a landfill in Afton, a predominantly Black and low-income community in Warren County, for disposing toxic PCB-contaminated soil from illegal dumping along NC roadways. Organized locally and by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, these acts of civil disobedience and free speech led to the arrests of over 500 people. While the demonstrations did not halt the landfill’s construction, they did catalyze several studies that examined the relationship between racial and environmental injustice, including the well-known Toxic Wastes and Race report by the United Church of Christ.

Source: https://www.ncfolk.org/2017/inside-nc-birthplace-of-environmental-justice/

In more recent years, up until July 2020, Northampton County was set to be home to a compressor station for the massive Atlantic Coast Pipeline—a now defunct fracked gas project of Duke and Dominion Energy. CWFNC was one of a dozen EJ organizations that filed a Title VI Civil Rights case against our NC Dept. of Environmental Quality for permitting the pipeline. CWFNC’s own Northeastern Organizer Belinda Joyner helped fight against the ACP’s intrusion in her home county. When asked about the communities in the county and her experiences with this struggle, Belinda explained, “Northampton County is a Tier 1 county, meaning that we are low-income. Being that we are a Tier 1, I feel that we are used as a dumping ground. Being about 58% African American, we are looked on as not being important.” She also pointed out that “[o]rganizing here in the county was not as I wanted it to be, because a lot of people looked at it [the ACP] as a done deal,” going on to explain how “[a] lot citizens from Halifax, Nash and other counties came together with a lot of help.” Ultimately, she felt “when the 3 states that would be affected by the ACP start[ed] working together, that was the turning point in defeating the ACP.”

Source: Belinda Joyner

Today, Hamlet, NC and nearby Dobbins Heights are predominantly Black communities in Richmond County currently facing a struggle against International Tie Disposal (ITD), a company that plans to build a biochar manufacturing facility. The facility would take in and burn creosote-treated railroad ties to create biochar through a process known as pyrolysis. Creosote is a known human carcinogen. Hamlet is already overburdened by massive polluting facilities, including a huge Enviva wood pellet mill, plastics manufacturers, steel fabricators and industrial animal operations, and Richmond County ranks 95th in health factors and 93rd in health outcomes when compared to other NC counties.

Source: Dogwood Alliance

North Carolinians have an opportunity to support each other NOW by speaking up for Hamlet and surrounding communities on Monday, March 1st at 6pm during the Dept. of Air Quality’s virtual public hearing on the proposed ITD air permit.

No community should be treated as a sacrifice zone. For information on how to join the hearing and register to comment, click here: https://deq.nc.gov/news/

(Featured image source: https://www.britannica.com/event/Greensboro-sit-in)