By: Lisa Sorg, NC Policy Watch

April 2, 2021

Public comment period ends Sunday on Optima TH’s air pollution permit for facility at Smithfield slaughterhouse

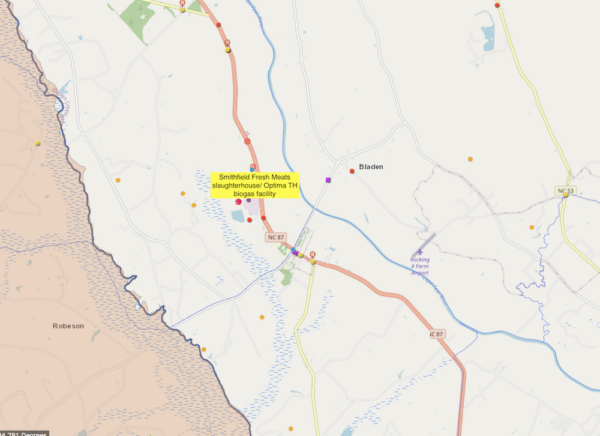

Optima TH has applied for a state air quality permit to operate a major biogas facility at Smithfield Fresh Meats in the Bladen County town of Tar Heel. If approved, Optima TH could emit 24,500 to 40,800 tons of greenhouse gases each year.

Biogas, in the form of methane, would be collected from Smithfield’s wastewater treatment system, upgraded onsite at the Optima TH facility to meet natural gas standards, and then injected into a Piedmont Natural Gas pipeline.

From there, Duke Energy would use the methane to generate energy at several of its former coal-fired plants, including H.F. Lee in Goldsboro, Sutton in Wilmington, and the Smith Energy Complex near Hamlet, according to Utilities Commission documents.

The Optima TH project is part of a larger and controversial push by Smithfield Foods, major utilities and the state lawmakers to promote swine waste-to-energy projects in eastern North Carolina. Most of these projects are in low-income neighborhoods or communities of color.

However, unlike the other projects, Optima TH doesn’t use swine waste from Smithfield farms. Instead, the gas is produced from the wastewater treatment plant at the Smithfield slaughterhouse. It is among the world’s largest, killing 35,000 hogs per day.

Before and after their death, hogs generate a lot of waste: not just urine and feces, but blood and other products of rendering that are sent to Smithfield’s wastewater treatment plant.

Whether from wastewater treatment plants or swine farms, biogas systems generally send methane to a pipeline. Other gases derived from the process that are not useful in energy production, such as carbon dioxide and hydrogen sulfide, are burned off through a “flare.”

The flare is the primary emissions source.

In addition to greenhouse gases, the Optima TH facility would emit 170 tons of sulfur dioxide annually, as well as lesser amounts of carbon monoxide, particulate matter and other pollutants, according to the company’s permit application.

Two big pollution sources at one location?

Because of the estimated amount of air pollutants, Optima TH’s permit would be placed in the Title V category, which is reserved for major emissions sources. Counting Smithfield’s own Title V permit, there would be two major polluters on the same property — in and near a low-income neighborhood and community of color.

Optima TH has been operating at the Smithfield plant since December 2019, albeit without an air permit. In January 2020, state regulators accidentally discovered the Optima facility while conducting a routine inspection of the slaughter plant.

Optima did not have an air permit, according to state records, because the company said it had an email from the Division of Air Quality stating it didn’t need one.

In June 2020, DAQ issued a Notice of Violation to Optima TH for failing to obtain an air permit, and directed the company to file an application — the one now under review.

Division of Air Quality spokeswoman Zaynab Nasif told Policy Watch that since Smithfield’s biogas flare was going offline in order to send biogas to Optima, there was no increase in net emissions. However, a permit was still required for Optima’s new flare.

The other incident of note was an odor complaint on Dec. 20, 2020, according to a state inspection conducted this year at the Smithfield slaughterhouse. However, according to Smithfield, the source of the odor was Optima. There are no records of a citation or enforcement action related to the odor.

Mark Maloney of Optima TH did not respond to an email and a phone call from Policy Watch about the facility’s operations or the proposed air permit.

Behind the scenes, though, state documents show that Smithfield and Optima TH successfully argued to state regulators for a more streamlined permitting process under the Clean Air Act.

Had Optima TH and Smithfield’s slaughterhouse been regulated as a single major emissions source, the project’s sulfur dioxide emissions would have required the permit to include a “Prevention of Significant Deterioration.”

PSD, as it’s known, would have required the installation of Best Available Control Technology, an air quality analysis, and an analysis of potential impacts of other pollution, as well as that of “associated growth.”

Associated growth is defined as additional residential, industrial and commercial developments — such as more biogas operations — that could be spurred by the new emissions source.

If Optima and Smithfield are regulated as two separate entities, with two separate Title V permits, they don’t have to account for the PSD rules.

State regulators evaluated three legal conditions, set out by the EPA, to determine if Smithfield and Optima TH are one or two facilities.

- If facilities are adjacent or contiguous;

- If the companies are under “common control”;

- And if they are in the same industrial grouping, or one serves as a “support facility” for the other.

The first criteria is clear: Smithfield is leasing land at its Tar Heel plant to Optima TH for the biogas facility.

But the other two criteria have more wiggle room.

Optima TH is buying all biogas generated at Smithfield, and there are no other suppliers for the facility. Smithfield dictates the amount of gas available, which would directly affect Optima’s emissions and compliance.

But DAQ wrote that it “believes this amounts to influence and not control, per EPA guidance,” and called the arrangement an “arm’s length contract.”

Neither Smithfield nor Optima TH has “control” over the other facility’s air pollution requirements, DAQ wrote.

Finally, although Smithfield and Optima are separate types of industries, the EPA does allow states to consider whether one functions as a “support facility.”

State regulators determined that the biogas project isn’t necessary for Smithfield to operate, although “there is no other function for Optima TH for locating on the Smithfield facility, except to process byproducts produced by Smithfield.”

There is no mandate for Optima to buy all the gas generated by Smithfield. And Smithfield has no contractual requirement to sell all the gas to Optima.

Thus, neither is a support facility, DAQ ruled.

(The state Department of Environmental Quality recently confronted the same legal considerations involving the proposed Align RNG plant near Turkey; again, DEQ determined, over many public objections, that Align RNG and its participating farms were separate entities.)

State energy law encourages industry growth

The expansion of North Carolina’s swine waste-to-gas industry is of the state’s own making. The 2007 Renewable Energy Portfolio Standard requires investor-owned utilities, such as Duke, to get a small percentage of their power from swine waste; after several delays in implementing the requirement, it is now 0.2% by 2023.

Gov. Cooper’s Clean Energy Plan also endorses swine waste-to-energy biogas, even though it comes with similar methane leakage issues from the pipelines as natural gas pulled from beneath the ground. Methane is an even more potent greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide, and a major driver of climate change.

Proponents of these biogas projects, including some farmers and local economic directors in hog-producing counties, have said in public hearings that selling the energy is another way for the growers to earn money. There has been no discussion, though, of the cost of installing these systems on individual farms — in many cases, upward of $500,000. Even with federal loans, the already cash-strapped farmers could go into deeper debt.

(A financial analysis of the state’s biogas potential, conducted by RTI in Research Triangle Park, was due in October of 2020; a spokesman said it was delayed by the pandemic, and should be released this spring.)

Two bills recently introduced in the legislature favor both natural gas and biogas. House Bill 220 would prohibit cities and counties from passing ordinances restricting the type of energy offered in new or existing construction. As Policy Watch reported earlier this month, versions of the measure have been introduced in at least 10 states. The propane and natural gas lobbies are behind the push, in reaction to actions by some California cities that no longer allow new natural gas connections because of the fuel’s link to climate change.

House Bill 271 would allow corporations, not just governments, to use eminent domain to build natural gas facilities and pipelines on private land. It passed the House 101-17, and will be heard next by the Senate Rules Committee.

Optima TH is one of several swine waste-to-energy projects in North Carolina. Optima KV, near Magnolia, in Duplin County, has been operating on a small scale since 2018.

Optima KV collects and upgrades biogas from five adjacent Smithfield farms through 40,000 feet of underground pipe, according to state records. Duke Energy also uses that biogas to meet the state’s renewable energy requirements for swine waste.

Because Optima KV’s total potential emissions are below 25 tons per year — 24.8 — the facility operates under more lenient rules approved by the Environmental Management Commission in 2016.

These rules allow many so-called “small emitters” to register their facilities with the state, while others aren’t required to obtain a permit at all. (They are subject to state inspection.)

Since its annual sulfur dioxide emissions exceed five tons — between 16 and 20 — Optima KV does have to register with the Division of Air Quality.

DAQ spokeswoman Nasif said Optima KV is required to track and report its emissions to ensure the facility complies with its registration requirements. It has done so, Nasif said.

Three months after Optima KV began operating, DAQ received an odor complaint from a nearby resident. The flare, which processes leftover “tail gas” that doesn’t enter the pipeline, had malfunctioned. The tail gas consists of carbon dioxide and hydrogen sulfide, the latter of which creates a “rotten egg” smell.

“When a flare operates properly there should be no odor,” state inspection records read. “But when not properly flared the tail gas “gives an offensive odor that is very pungent … Optima is working to resolve this quickly and understands that the migration of raw hydrogen sulfide is considered a nuisance order and brings them out of compliance.”

No complaints have been filed against Optima KV in the last two years, according to state records.

Optima KV is managed by Gus Simmons, a member of the state Energy Policy Council. He is also an engineer with Cavanaugh & Associates, which is consulting on the Align RNG project in Duplin and Sampson counties.

A partnership between Dominion Energy and Smithfield Foods, Align RNG is the largest swine-to-waste project so far in the state. It would funnel gas from 19 farms through 30 miles of pipeline over two counties, to a conditioning facility on Highway 24 near Turkey.

Smithfield has refused to disclose the location of 15 of the operations, even to state regulators.

Nonetheless, yesterday, the Division of Water Resources did approve modified permits for the four known farms. Three will install new, synthetically lined and covered anaerobic digesters. A fourth will cover an existing lagoon to capture the methane.

All of them are corporate Smithfield farms, not contract growers: Waters/M&M Rivenbark, Benson, and 2037 & 2038 Farm, and Kilpatrick/Merritt account for 43,000 hogs.

The state is requiring some of the farms to sample the waste for pathogens and nutrients, such as nitrogen, each quarter. Others are required to add buffers or other improvements to the spray fields to reduce the risk of offsite runoff to neighboring properties.

Environmental advocates express concern

A position paper issued this week by several environmental groups criticized the Clean Energy Plan for failing to acknowledge the environmental and public health impacts of these enormous hog farms and the biogas projects associated with them.

The groups — including the NC Conservation Network, several river keeper groups, Environmental Justice Community Action Network, the Down East Coal Ash Environmental and Social Justice Coalition, and REACH — said biogas projects from hog farms increase the threat of water pollution.

Covering a waste lagoon increases the concentration of ammonia in the liquid waste that will still be sprayed onto cropland and often runs off into our surface waters or seeps into groundwater, the groups said. It also increases downward pressure on unlined lagoons.

“Directed biogas projects are even worse, as methane leakage during digestion, transport, and storage may mitigate any supposed climate benefits while constructing pipelines may destroy wetlands which provide important protections against flooding.”